How can something intangible (credit) matter more than a real resource (oil)?

I just finished a book that changed, or at least makes more dynamic, the way I view African development, Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. Sometimes we get so ensnared in the details of social analysis that we forget to take a step back and look at the larger picture. Harari’s historical account helps us to do just that. His research deepens our understanding of the complexities of the resource course in oil-rich nations without strong democratic institutions.

He argues that one of the key turning points in human history was when we stopped viewing world resources and money as finite, and instead recognized that trust in imaginary future goods could create infinite economic expansion. These imaginary future goods were represented with a new kind of money: CREDIT.

Although we hear of the dark side of credit often—consumer credit card debt, credit on a loan to buy a home that the consumer could never pay off—credit is actually miraculous. As Harari phrases it, “credit enables us to build the present at the expense of the future.” In it, there is implicit hope that future resources will be more bountiful than current ones. That hope in the hypothetical is just so….human. And it has allowed the world’s per capita production to grow at a staggering rate over the last several centuries.

Although he doesn’t mention Nigeria specifically, a section of the book lucidly argues that a country’s credit rating, or the shared belief that a country will pay back its debts, matters more to its economic development than any other factor—including natural resource endowments.

Here is a grossly over simplified explanation using a feedback loop of why a nation’s healthy credit matters so much:

A) People have faith in the future economy —> B) credit is given out —> C) credit allows us to grow current businesses —> D) this growth is invested in new businesses —> E) businesses create goods that can be sold to pay back loans to creditors —> F) these pay backs fortify faith in the future economy.

And we are now back at the beginning of this cycle.

For those familiar with Nigeria’s economic history, any moment in this cycle can be, and has been, interrupted because of its unhealthy oil economy. In 2004, Nigeria required international debt relief after sovereign defaults on what it owed to the IMF. This was due to “heavy borrowing, rising interest rates, and inefficient trade” (see D). When the country suspended the national fuel subsidy in January 2012, no one wanted to expand their businesses that required gasoline, which is all of them since electricity is unreliable (see D). As I have mentioned in another post, oil can create a dangerous mono-economy in developing countries because it replaces the drive to produce anything aside from the oil itself (see E). Because so much of Nigeria’s economy is based on oil, its unstable pricing erodes the “faith in the future economy” that is the basis of credit extensions at all (see A).

Here is the excerpt of Sapiens that struck me as so pertinent to Nigeria:

A country’s credit rating is far more important to its economic well-being than are its natural resources. Credit ratings indicate the probability that a country will pay its debts. In addition to purely economic data, they take into account political, social and even cultural factors. An oil-rich country cursed with a despotic government, endemic warfare and a corrupt judicial system will usually receive a low credit rating. As a result, it is likely remain relatively poor since it will not be able to raise the necessary capital to make the most of its oil bounty.

Based on the description below, would you trust Nigeria to pay back money you gave it as a loan? Or as a business owner, would you trust its economy to grow, and give you returns on a new business you started with money you got from a creditor? Not many people would.

What is a country’s credit rating anyway?

In general, a credit rating is used by sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and other investors to gauge the credit worthiness of a country—thus having a big impact on the country’s borrowing costs.

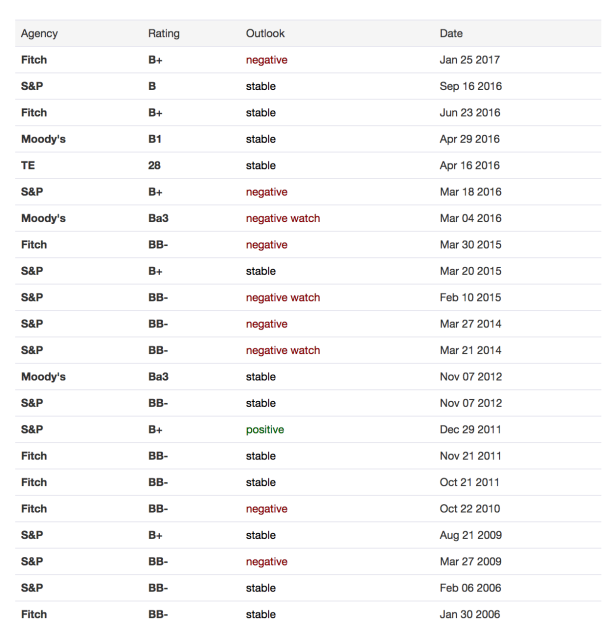

Standard & Poor’s credit rating for Nigeria stands at B with stable outlook. Moody’s credit rating for Nigeria was last set at B1 with stable outlook. Fitch’s credit rating for Nigeria was last reported at B+ with negative outlook. Overall, there are 11 ratings of stable, 9 rating of negative, and just rating of positive for Nigeria

As an aside, anyone who witnessed the 2008 American economic meltdown based on home loans can appreciate that these credit ratings are hypothetical. All of those agencies above, those “experts,” failed to change their credit ratings, which could have helped alleviate the devastating U.S. housing crisis that negatively impacted every country in the world.

So, if Nigerian policy makers are to take Harari’s purely academic arguments to heart, they’ll stop writing checks they can’t cash and pay back creditors.

Trust matters.

I wasn’t aware of this credit rating concept and now I’m sure I can explain it well to another person. Thanks for the blog, it highlights an important concept not only to Nigeria’s growth but also many other African countries. However, I feel like Nigeria stopping to write the checks they can’t cash and pay back creditors instead can only be possible if this country is able to raise the money need to pay which also might push them to ask for loans to pay loans. Another alternative is to optimise their oil industry but it’s also limited by less capital. I feel like this is a cycle that can be solved by economic and political stability; which is a journey and also a diverse economy. Mono-economy is also a threat in this case.

LikeLike

Divine, you are absolutely correct that diversified economies create stability and monoeconomies create instability. Additionally, you brought out the salient point that inability to pay back loans impacts our confidence in a country. Confidence is a belief, but it drives behaviors with measurable impacts.

LikeLike

Fascinating article here!

I can see why credit and its rating matter a lot. I like how Harari describes credit as what enables us to build the present at the expense of the future, with its foundation in an intangible commodity: hope. As you have duly cited, the “dark side” of credit exists as well, in parallel. In several cases, does this not play a major part in the scheme to make the poor poorer and the rich richer, furthering economic inequality? Maybe this con doesn’t outweigh the pros.

To come to Nigeria’s case, credit rating does matter more than oil because it could amplify faith in the economy, businesses and investments could thrive, it is more likely to get on the good sides of members of the international community, and oil prices are not the most stable all the time. Nonetheless, if credit ratings indicate that a nation would pay its debts back, to what end? If, among many reasons, it is so it could borrow some more for “next time”, doesn’t this point to a greater economic challenge existing within the country?

Oil could matter more because it’s the reason there was any interest in Nigeria in the first place; it attracted global eyes. Oil could matter more because it’s able to contribute to alleviating the effects of a tarnished credit rating reputation (by using its resources to pay back debt). An oil-rich country may be “cursed with a despotic government, endemic warfare and a corrupt judicial system” (and don’t get me wrong, I don’t deny that; heck, I won’t fully trust Nigeria to pay me back on a loan either), but oil could matter more because with or without the presence of faith, hope, and trust, the resource remains and possesses tangible, albeit fluctuating, value.

But, at the end of the day, they mightn’t be mutually exclusive; if oil were handled properly and intelligently, I speculate the country’s credit rating would rise alongside, and they would both matter hand in hand.

LikeLike

Your well-written response speaks to the point that I made on our very first session: traditional economics is largely the study of ideas about human socioeconomic behavior–forecasts about what people should do in perfect systems, models of what should happen under certain conditions (but it rarely pans out these ways!). Your response expanded on the idea that economics is about setting expectations, perceptions, and ideas that then, in turn, actually can change realities and real outcomes. Well done.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wanted to leave a comment and read this piece, and it just reflected what I wanted to say. I couldn’t have said it in a better way. Chimfeka O, to reflect on what he says, it all comes back to his first paragraph, whether credit rating is good economically or whether the natural resources takes over, it doesn’t really help as long as this system that benefits the inequalities between rich and poor, which destabilizes the countries and its exploitation of its resources exist.

LikeLike

“Credit enables us to build the present at the expense of the Future”

Let me start by saying that your Blog is worth the discussion. As a current Global Challenges Student, seeing the way you articulate issues, it gives me hope that we have enough to pass down to the next generation.

There are but many highlights from this particular post; and I must admit that I cant wait to go through all of your collection. # disclaimer. I might not be the best expert when it comes to Economic Discuss, but I do have a few things I disagree with.

While at the same time I have great respect for your line of work, I just hope you will help me Understand in person some of the terms used and why?

First Question: I believe that Credit rating does not put food on the table. Yes, this can be contextualized in a different way, But my question Is How many African Countries do you know probably form experience that has experienced economic growth because of their credit ratings?

Second Question: In the post, you mentioned that “oil can create a dangerous mono-economy in developing countries because it replaces the drive to produce anything aside from the oil itself”

I believe this could be a great opportunity for Nigeria to Master its craft. With the little I know, there are countries in the world that are best known for their areas of expertise. The rest of the Arab world did not develop because of Credit Ratings, Nor did they become decorated based on the amount of Water or Diamond they have. As for a fact, history shows that the Arabs came to form nothing before the 16th and 17th century. However, they made the best of what they have by recognizing the #LITTLE

As I said, I might not be the best expert regarding such matters, but just to spice up the knowledge Bank, I believe that Nigeria like you advised should start creating sustainable measure at which the Oil they have should be valued by the rest of world. #My People mek we stop D Fighting ohh” . Another example id my country Sierra Leone, I might complete an entire book if I should list the natural resources Sierra Leone has. yet we still rely on foreign aid.

If only Africa can realize the need to make a DIFFERENCE with the DIFFERENT then we can start talking about Credit Ratings. But until then there are weightier matters beyond Credit Ratings.

Albert Paul Moifula

3-year Global Challenges Student

African Leadership University Rwanda.

LikeLike

You make an excellent point about expertise (in oil), Albert. Economists call this “comparative advantage.” Comparative advantage is the idea that countries that do a certain thing well should focus on that one thing, and then that creates overall systemic efficiency.

A notable difference is that some “oil expert” Gulf Arab States, e.g. UAE, Qatar, used oil profits to in turn invest in other economic projects that diversified their economies. UAE built itself a tourism sector from scratch, for example. UAE is an example of an economy using oil profits to then diversify, which Nigeria has not done. Consider what African countries’ have as their comparative advantage and how that should be galvanized.

LikeLike

Wow, I never thought credit could have such an impact on a nation’s economy!! Great read and unfortunately, I don’t have anything to disagree with here! Hahaha

LikeLike

Ian, this is a much better response than trying to come up with a disagreement without empirical evidence! Yes, a country’s credit rating is vital. Consider what variables inform that rating, and how those variables differ in Africa compared to other world regions.

LikeLike

I think that the bigger picture is always good to look at. However, the issue of how why Nigeria cannot afford to pay back their debts should be the most significant concern for me. Even if we were to look at credit as a useful tool to give hope to people to generate wealth for future generations, won’t future generations not be in turn impacted by its inability to pay back their debts due to corrupt leaders and the mismanagement of oil resources, such as in Nigeria? Another thing I do agree with is the need for Nigeria to diversify its economy so as not to become too heavily reliant on oil. How can they use other resources to generate power, for example? From my perspective, considering the theories that abound from experts, I would not give Nigeria credit because even the system at play is not trustworthy enough within itself to generate the profits to pay me back my money. Why should you rely on oil with the abundance of technology and brilliant minds?

Therefore, I do not think that its credit rating should be overlooked over long term sustainability and growth of the economy through the diversification of resources.

LikeLike

Very well-reasoned, Joy. You are the first commenter to mention the importance of diversification of an economy. This is vital for stability, financing for social services, political forecasting, and lowering rates of corruption (monoeconomies are very often positively linked to corruption). Diversification of the economy, which leads to socio-economic stability, is also linked to lower rates of civil unrest and mass violence because citizens have more confidence in their future outcomes.

LikeLike

I’m of the opinion that a country’s credit rating can be directly influenced by its management of resources/endowments. It is likely impossible to achieve a higher credit rating without ongoing economic development and investment going on in the country. This is because most creditors look at the assets a country has and its prospective development to determine if they can pay back the loan or not

LikeLike

Yes, and this creates a cycle of poverty. It begs the question: A country needs ongoing economic investment to produce outcomes that improve its credit rating, but how can it initially start those investments without a solid credit rating, to begin with? No one has a conclusive solution.

LikeLike

I agree that Nigeria should pay back their loans instead of keeping borrowing in hopes that the future will become Better. However, all of this is based on corruption in the country, starting from the government to the citizens. Based on that, why would the IMF continue giving loans since they know that Nigerians will not be able to pay back in the long run. What profits do they get from constantly giving Loan To them? That aside, Nigeria is a developing country which has faced a lot of corruption and bad governance. At the moment, it may not look like a trustworthy place to start a business , but through hard work and a new governance system, the economy will get better a businesss.

LikeLike

I agree with everything you wrote and let’s take it a step further. What is the relationship between international loans and the rates of corruption in Nigeria? Do loans cause, contribute to, or just happen to coincide with corruption? One could argue causality, but others could point out the correlation (e.g. the type of country that needs loans is also the type of country that has corruption), and still others may identify an “omitted third variable” (e.g. lack of polling stations in rural Nigeria leads to incapable politicians being elected, and those politicians cause both unfavorable loan packages and corruption, for example). Political economy is fascinating because is difficult to ever prove conclusively these mechanisms.

LikeLike

I agree that a country’s credit ratings matter more than its economic resources. This is because, even if a country is rich in resources and has a low credit rating, there is a chance that it is caused by instability or poor governance. This means that no one would want to trade with them and so, the natural resources go unexploited, hence not very useful.

LikeLike

This is an interesting read Laine, I am of the view that although credit ratings are important; they should be set aside. Particularly for African countries, where we have who evade accountability at every corner. These credit ratings have led to countries suffering from irrecoverable debts, leaving the ordinary citizen in poverty and financially impossible situations due to inflation as countries try their best to grow their dying economies.

As such, I would like to bring up the fact that the loans and grants received as aid in this case often have hidden sentiments to pursue the funder/aider’s agenda. At this point I would like to suggest that Africa adopt some of the result oriented practices of western and eastern economies and develop an appropriate mixed economic system with the aide of the existent traditional systems to promote intra-Africa economic growth without having to lend from external parties. But then again, this will depend on regional integration becoming a success; which is highly impossible if the African Union is still receiving funding from the said external parties. It is my assumption that each transaction has terms and conditions, and those terms and conditions set by the African Union’s funders are not ideal for the growth of the African economy.

LikeLike

It sounds like you are a proponent of endogenous growth for African countries over exogenous growth, and that you advocate for regionalism/domestic focus over globalization. You are in good company among many African development economists, Manno. Consider if there just needs to be reform in international aid and loans, or if it should be avoided altogether. Think of alternative measurements of an African country’s loan/aid/investment worthiness if we are to set aside credit scores. I agree that credit ratings can be misleading and entail historical baggage that hurts African countries. I would say we just need an alternative way to assess if we don’t use credit ratings.

LikeLike

Well done on this, and I wish most economists would read the piece. However, I’m sensing many factors held constant. First, not all African countries like Nigeria have enough oil/natural resources to act as alternatives to credits. Some states don’t have any other choice but to take credits to push economic advancement, and we’ve seen success stories where all debts well paid or the dependency on them [ credits] have slowed down. Second, if credits are invested in growing businesses, and management of these businesses is assessed continuously to ensure the payment of the credits on time, in the long-run, it would mean that the country will own the business initiated from credits. So yes, countries may go back at the beginning of this cycle in a short time, but in the long-run, there could be some benefits. I guess the point I’m trying to make is that management of the acquired credits remains vital in receiving credits and payments, and it’s a concept that can be explored on its own. Poor management could lead to the failure of compensation and Vice-versa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said. You are describing the cycle of loans and their repayments. The main thing I would add is that there must be an “enforcement mechanism” in place to monitor and measure repayment. A pressing question in this cycle you have described is: What form should this enforcement mechanism take and who should be the actors responsible for this mechanism? We will discuss this more in our week on government regulation.

LikeLike

Great work on this Laine. I look forward to also reading the book in order to get more insights on Harari’s thoughts about the importance of credit ratings.

Generally, the concept of credit isn’t evil. However, it requires careful planning and accurate forecasting, especially on the borrower’s side, or otherwise, the economy of future generations will be jeopardized. Some governments have taken huge loans which have ended up negatively affecting succeeding governments. One question remains though, who benefits more between the issuer of loans and the recipient government?

While I completely understand the need for a business loan, I am yet to understand why loans should be taken to finance non-profitable development projects such as roads. Is this how America, China, Singapore, Germany, the UK, Japan – just to mention a few – were built?

LikeLike

This is a good question, Moses. I will say that loans and aid rebuilt Western Europe and parts of Japan in the decade after WWII. This rebuilding of Europe was considered a humanitarian endeavor as well as effort to get Europe back as a key economic trade partner for the U.S. The four Asian tigers-Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan-largely pulled themselves out of policy using new economic policies. The incentives behind loans to African countries may (or may not?) but very different. Consider the differences in the incentives for loans for development projects in Africa today versus Europe in the 1950s.

LikeLike

Thank you for this insightful article Laine! I really enjoyed reading it (and I am not exactly an enthusiast about economics). Nigeria’s economy has been so dependent on its oil that other booming sectors with potential (such as Agriculture) have suffered. The oil has indisputably helped Nigeria get to the level it is today, however, it is still a finite resource, meaning it can become scarce or will eventually be exhausted. Nigeria has to make sure it starts to leverage other sectors to diversify its economy, as soon as possible, because it may become devastating to the economy if they do not have any alternatives when the inevitable happens. I understand though that the human nature of adaptation will eventually kick in, but what happens before then?

I do agree that credit ratings are extremely important for a country’s development, especially with third world countries. Even with the resources present in many of these third world countries, they still haven’t been able to develop themselves without some sort of foreign aid.

In my opinion, however, I think that currently in Nigeria, Oil is still more important than credit ratings, just because it’s such a needed resource everywhere in the world. Although the country’s rating is already average to low, as seen from the above article, I just think it cannot go any lower than that because the country still has oil that the international community needs. Perhaps if the oil starts getting depleted/exhausted without Nigeria diversifying its economy, then the credit ratings could become worse and more important, as the international community will have nothing to lose. Again, this is just my opinion and not based on any fact!

LikeLike

Nigeria is in such an unfortunate situation. Her low credit rating won’t enable her to acquire a sufficient amount of loans needed to foster tangible development. Furthermore, when we consider the fact that Nigeria is currently in a lot of debt the question of where or how they will acquire the money to pay their debts because scary. I believe rather than relying on securing loans to offset old debts, Nigeria should focus on developing systems that will enable them to harness its human and natural resources effectively. Through this, they will be able to acquire the needed money to pay back their old loans and move on a new path where they don’t have to keep relying on loans and foreign aids

LikeLike

Brief but impressive content @Deltalaine.

Now to the real business. Why do we always focus on the good side of something and sometimes ignoring its consequences? Is this not why Africa is still struggling to address its problems?

Drawing from a personal point of view, I believe that every existing material on earth has it used and fulfills its creation purpose. Talking about credit, it plays a significant role in supporting individuals in society to start a business and engage in a diverse number of activities that require loans or credit to pick a stance. It also helps governments strengthen their economies by building infrastructures, investing in technologies and transportation, and improving education systems, among others – we are aware of these.

But speaking of this word, “credit,” how many African country has a developed economy with all their monthly or yearly credit? How many have alleviated poverty and inequality? How many have paid their debts and using their own finance for economic development? I still doubt if any do exist.

I’m not favoring any of the two (credit nor oil) because they perform different functions. The sad truth is, utilizing natural resources such as oil has a significant role to play when it comes to economic growth and development through forex – that is, collecting items and give money in return for them to be yours – not the one of loan or credit that will leave you unrested until you repay your debts. Not overlooking the opposite side of such natural resources like oil, high dependence on it over other natural resources crushes and seriously damages an economy, which I think is affecting Nigeria due to their fixed focus on oil compared to other natural resources.

LikeLike